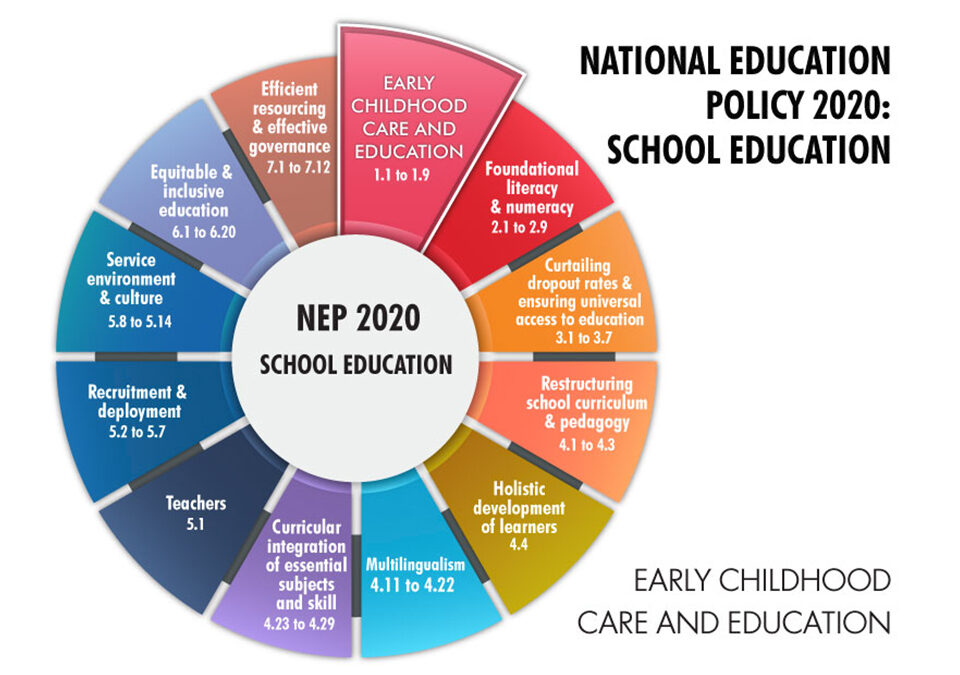

GLIMPSE OF NEP 2020: New Education Policy

The Key Features of a 21st Century Classroom

January 21, 2022

How can innovative teaching strategies benefit students?

January 21, 2022The new education policy has deservedly been at the center of discussion in educational circles. The NEP 2020 is expected to bring about systemic changes in the way education is structured, and it is also going to alter the methodologies and broaden the outcomes of school certificates, degrees, and diplomas.

The parliament approved NEP 2020 in July, and the implementation is already underway. It is a colossal project and will take effect in phases. To begin with, the NEP’s precursor of sorts, the National Curriculum Framework (NCF), will be put in place and its implementation ensured.

There are both broad shifts and finer points in the NEP draft. The points that leap to the eye include the statutory enforcement of the mother tongue as the medium of instruction in the pre-primary and primary classes, the change of the school education format from the longstanding 10+2 to the proposed 5+3+3+4, the removal of the M.Phil. program, the flexibility in the choice of undergraduate courses coupled with the freedom to change one’s mind about them.

The commentators have long been saying that the education system in India needs reform. It is said that the current format and modalities of education, especially at the school level, predispose students to information-intensive learning patterns and limit imagination and creativity. Moreover, the conventional system relies solely on “standardized” assessments to measure learning outcomes. The teachers and students in such a learning environment have little incentive to innovate, imagine or create. There are systemic gaps, too, the most glaring of which concerns early childhood education, numeracy literacy, teacher training, special education, and adult education. It is indeed ambitious for any overarching policy to address all of these issues and bring about a measurable change.

Universal education in India has succeeded in drastically improving enrollment rates. However, the dropout rates post-primary remain a concern. The NEP concedes in principle to the inevitability of the flux of technology in the Indian education system. AI, VR, AR, and blockchain have been identified as useful and promising avenues.

Replacing the education policy of 1986, NEP 2020 aims to enhance access, equity, quality, affordability, and accountability in education. Society and the economy have seen major shifts in the decades since the National Education Policy in India was last revised (1986). It is hard to dispute that we needed a comprehensive and sweeping review; hopefully, it has arrived.

Let’s take a look at the important features and implications of the NEP 2020

- The 10+2 structure will change into a 5+3+3+4 structure. This means that early childhood education has been integrated into formal schooling. It’s being called the foundational stage (3yrs-8yrs). Hitherto, the ECE has not been formalized and was only loosely regulated. With imminent changes, things will change.

- The policy seeks to ensure that education does not remain so monolingual, with a strong bias in favor of English at the expense of Indian languages. To that end, the native languages will make a phased entry as media of instruction in the primary classes.

- The assessments at the school level will become more regular, moving away from 10th and 12th exclusive watersheds. The students will also have to take standardized exams in classes 3, 5, and 8.

- The scholastic career-defining board exams will be made more comprehensive, focusing on testing conceptual understanding rather than information reproduction. The results will become less restrictive as the students will be allowed to take improvement exams.

- Students at the secondary stage will have more choices of subjects.

- The undergraduate degree will have more choices of subjects, and the boundaries of streams will be somewhat porous. Besides that, there will be exit options available to students at defined points in the course. The rigid separation between Sciences, Humanities, and Arts, and that between academic and vocational, will be done away with, and choices will be available across streams.

- The aspirational setpoint is 2040, by which time all higher educational institutions are expected to become multi-disciplinary. By 2030 all the universities will have teacher education departments.

- The B.Ed program will be for 4 years, and a merit-based scholarship will be introduced.

- The Teacher Eligibility Tests (TETs) will be made more comprehensive, and test scores will be applicable while recruitment.

- Teachers will have to attend workshops for professional development with 50 hours of mandatory participation per year.

- National Higher Education Regulatory Council (NHERC) will exclusively regulate higher education except for legal and medical education. The higher Education Commission of India (HECI) will oversee the formulation of distinct regulatory mechanisms for regulation, accreditation, academic standard-setting, and funding.

- Graded autonomy will be given to colleges, basis the accreditation assessments

- Indian Universities could set up international campuses after reaching a performance threshold. Likewise, select top 100 foreign universities will be allowed to operate on Indian soil.

A look at some notable international education systems

It is instructive to look at international education scenarios to understand the global environment that necessitated certain very specific changes in our education policy. Let’s look at the state of education in the developed world.

Singapore

The country spends 12.8 billion Dollars on education every year. While the latest national reforms in education in Singapore came in 2018, the Compulsory Education Act of 2000 is considered by observers a milestone in the educational history of the Southeast Asian nation. The said act made denial or neglect of child education a criminal offense, with the only exceptions being children with severe disabilities. The curriculum framework emphasizes 21st-century skill development and critical thinking. Assessments are comprehensive and highly standardized. At the same time, they are highly diverse. The schools enjoy considerable autonomy in curriculum design and implementation.

Teacher training is prioritized, and 100 hrs of training is mandatory per year.

Australia

Called ‘Student First’, the recent-most educational policy concerning education in Australia came in 2014. The land down under is the world’s third-largest provider of international education and spends 5.9 % of GDP on education. Like all progressive education models, the Australian model also places a premium on learning outcomes, high participation levels, and emotional and social well-being. The schooling structure across the country consists of foundation or early childhood education years followed by 12 additional years of schooling. The policies to give impetus to adult education are also in place. The states primarily deal with education with funding from the center.

The Australian Qualifications Framework, enforced in 1995, sets the qualification requirements for degree programs in Australia. Australian Curriculum (2010), revised periodically, is in force in the schools.

The country emphasizes internationalization in education and enhancing access to the labor market. The schools are incentivized by granting increased autonomy, ensuring wider community participation in child education.

United States

The US has not been a standard-bearer of academic excellence for decades now. This is even though the superpower spends most per capita on education. While there exists a rough equivalent to our proposed national curriculum framework in the form of Common Core, education is primarily catered to by the states and local governments.

The US has seen a lot of experiments in early childhood and primary education and has a diverse educational ecosystem. It is one of the most important hosts for international students and is home to the world’s finest universities and colleges.

Teacher training is an important criterion in professional development, and teachers with regular training are incentivized with steady growth.

Finland

Arguably the most talked-about education system in the world, the education system in Finland serves as a model for emulation for governments across the world. The systemic reforms have placed the Nordic nation in good stead for years, and one of the finest Human Development Index is a testimony, in part, of the efficacy and sustainability of the education system of this country.

Finland has an impressive 12.2 Billion Euros in the education budget.

Again, the overarching theme in education is student-centeredness and 21st-century skill development with reasonable autonomy for teachers with a wide latitude given to curriculum designers and implementers. The well-being of students is deeply ingrained in the system, and learning styles are emphasized instead of rigidly standard frameworks. Assessments are imaginative, and the same is the pedagogy. Finnish schooling has arguably brought currency and meaning to the terms like the joy of learning and collaborative instruction.

Finnish education structure looks something like this—it begins early with a structured daycare network followed by a yearlong preschooling and then comes a nine yearlong basic comprehensive schooling. The schooling culminates, generally speaking, with secondary general academic and vocational education. Thereafter begins higher education.

Remarkably, the students are not streamed or systematically graded in the nine years of their comprehensive schooling. Finland has an exceptional inclusive education model in place, which has an exemplary record of mainstreaming students by minimizing low scholastic achievement.

Russia

Russia is the OECD country that stands out with its remarkably small class sizes and shortest hour-span of instruction. Education is skill-oriented, and technical education can be called the backbone of the system. Education is the mandate of the states, with federal laws to oversee them.

Notably, the country spends 3.6 % of its GDP on education, which is lower than the OECD average of 5.2%.

England

Despite the reforms brought in by the Education Act of 2002, the British education system is highly achievement-oriented. The reflections of the system can be seen in our education system at times. Formal schooling is compulsory and applies to children between the ages of 5 and 18. The national curriculum of England focuses on academic achievement and vocational excellence. Progressive waves have brought in the incentivization of creativity and imagination. Subjects are allocated to specific grades by the guidelines of the national curriculum.

The schools in England have historically pushed the case for greater autonomy, and it has been granted in some measure. The Office of Standards in Education and Child Services assesses the standards of schools.

While the new National Education Policy has recommended increasing expenditure on education by 2 percentage points i.e. from 4 to 6 percent GDP at the earliest, it may take years before we can match the education expenditure of developed nations in absolute terms. This being true, India can aspire to match the global standards of quality and innovation by roping in progressive individuals and organizations to adopt best practices and innovate. The Indian public education system in the world is the second largest in the world. India’s private school system is a 23-billion-dollar industry. These data points testify to the potential of the sector and the need for initiative, participation, and direction. The education service providers also have an important role to play, and the adoption of technology by schools has to be fast-tracked. The COVID-19 crisis has incidentally brought about an awakening of sorts in the policymakers about the digital divide and the need for digitization in education processes on a relevant scale. Teacher training is another area that needs to be streamlined and controlled for quality.

With NEP in the offing, we may finally see substantive changes in the education system in the coming years.

Follow us on